Artists’ wellbeing: Sustaining artists working with trauma impacted communities

When artist’s are called upon to work in remote or trauma affected communities, the impacts can be intense, usually without access to the psychological services available to other support agencies. So how do artist’s find the balance between dealing with a community’s trauma and their own self-care?

In this episode of Creative Responders, Scotia Monkivitch takes listeners into the beautiful Jarrah Karri Marri forest in Western Australia, walking among striking charcoal sculptures with Fiona Sinclair, manager of the Understory Art and Nature Trail.

We also speak to seasoned arts worker Karen Hethey and psychologist Shona Erskine to ask the question – what can artist’s do for themselves, but also, what structural changes do we need to see in the sector to make practice safer for artists and community cultural development workers?

Interviewees:

Fiona Sinclair, Instigator and Manager of the Understory Art and Nature Trail

Karen Hethey, an artist working with community whose practice draws on a professional background in puppetry arts, performance making, intercultural community arts and applied Anthropology

Doctor Shona Erskine, a registered psychologist and consultant who works closely with organisations and artists, coaching to build resilience and to enhance performance

WA Making Time: Artist Self-care Retreat participants – Jodie Davidson and Julian Canny

Production Credits:

Produced in association with Audiocraft with Executive Producer, Jess O’Callaghan, Producer, Selena Shannon and Creative Recovery Network Project Manager, Jill Robson. Sound Engineer is Tiffany Dimmack.

Related links

Episode 4 Transcript

Artist’s Well-Being: Sustaining artists working with trauma impacted communities

We would like to acknowledge the traditional owners on whose land this podcast was produced and pay our respects to their elders past and present. We would also like to acknowledge the commitment and sacrifice of First Nations people in the preservation of country and culture. This was and always will be Aboriginal land.

SFX: Forest sounds, birds

FIONA: In winter you might come and it might be blustery and cold and rainy. And in Summer it can be really hot, and the birds change, and the air is different depending on the moisture levels, it’s never the same. Whereas a gallery is constant, humans like to control things. This is a wild place.

SCOTIA: Fiona Sinclair has managed the Understory Art and Nature Trail ever since it launched in 2006.

SFX: Forest walking in background…

FIONA: There is a considerable amount of maintenance work when you operate an art trail in the forest…

SCOTIA: Combining art and nature is central to her practice as an artist.

FIONA: So the walk that we’re on is a 1.2km walk trail, very easy going walk trail through pristine native forest. Along the walk trail, we have sculptures, over 50 artworks. And they all are site specific. They’re all in relation to this particular little patch of paradise…

SFX: Forest walking, Fiona and Scotia pointing out artworks

FIONA: Oh that’s one of my husband’s, it’s incredibly nepotistic!

SCOTIA: I’m Scotia Monkivitch from the Creative Recovery Network and this episode of Creative Responders takes us to the bottom of Western Australia.

So far in this series we’ve heard about how art and creativity can strengthen disaster preparedness and recovery – how it engaged children in the recovery process following Black Saturday, galvanised a community in the wake of Cyclone Yasi, and helped farmers combat isolation during drought.

But this time, we’re turning the microphone around on the artists. To work effectively with trauma affected communities, artists need to be cared for just like any other part of the system.

In this episode we’ll hear about what artists can do for themselves, but also what structural changes we need to see in the sector to make their practise safer.

FIONA: My name is Fiona Sinclair, I live in a really small community in the south west of WA called Northcliffe, in the beautiful Jarrah Karri Marri forest. I’m an artist, I’m an artist worker, I’m an arts lover, and also a lover of being in a small community in regional Australia.

SCOTIA: Northcliffe is about four hours South of Perth, near the south-facing coast of Western Australia, the land of the Noongar peoples. This part of the state is covered by the tallest trees in the country.

FIONA: I moved here just over 20 years ago with my husband, we ended up in this part of the world because as an artist he is very connected to this particular type of vegetation, this weather system, the history of this area, and his work relies on being close to that.

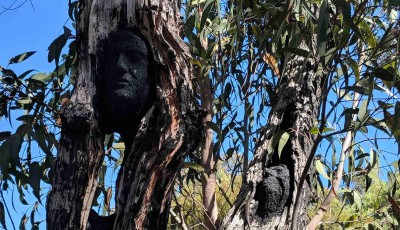

SCOTIA: The Understory Art and Nature Trail is enriched with motifs of the Northcliffe community… One recurring artwork is a series of sculptures by artist Kim Perrier.

FIONA: So here you have some more of Kim’s work. These are various faces, can you see them in the trees?

SCOTIA: The sculptures are moulds of Northcliffe locals. Their heads and bodies were cast and then reproduced in dry, black, charcoal, and fixed to the trees.

SCOTIA: There is a harmony between the living bush and the works of art as you walk the trail, but for Fiona this journey hasn’t always been a peaceful ride.

FIONA: The Understory trail evolved out of a really difficult time in our local community where there was two main industries in rapid decline and actual deregulation. The Dairy industry and the Timber industry. The two bedrock industries of our community and they both closed within a year of each other.

SCOTIA: The economic uncertainty caused the town to divide on the issue of new logging.

FIONA: So some people wanted to see no more logging in old growth forests and the people who were aligned with the timber industry wanted to keep it going. And that on a cerebral head level sounds like maybe they could sit in a room and talk about it but on a day to day level it means you can only shop in some shops if you are conservation. You can only go to other shops if you’re not. You know, our local environment centre frequently was firebombed. You just get abused, animal remains would be thrown against shop doors. It was horrible, very very divided, quite violent, very personalised attacks.

FIONA: We were very obviously a community in decline. So you know governments were prepared to consider options for new futures.

SCOTIA: Fiona saw an opportunity. The town desperately needed to be invigorated. An arts nature trail might provide a small tourist economy. But more than that, the project could provide a space for common ground to be found in the community.

FIONA: I did have a really strong feeling that I could play a role in helping our community to rebuild. And one of the things that I thought I could offer was a way of sharing stories.

SCOTIA: With the help of other artists, Fiona curated and launched the nature trail, supported the development of an adjacent gallery space and paved the way for more arts events in the area. All while negotiating the politics of the broken town, and slowly bridging the divide.

FIONA: It was a slow process because there’s a lot of distrust in a polarised community that has been really aggressively violent towards each other over a period of many years. It was a slow process based on personal conversations, one on one, trying to unlock resistance and see what we could transform as opportunity.

SCOTIA: Every year Fiona scrambles to secure funding to keep the trail and other community arts projects going. But her total workload is more than the sum of its parts. Many hours of unpaid work. Significant emotional labour. With minimal support structures.

FIONA: I can’t even…I can’t even imagine how much time I volunteer to be honest.

SCOTIA: A forest gallery doesn’t close at 5pm. Storms damage the path. Trees fall over and crush artworks…

For years, Fiona was at the beck and call of nature. Then the town took another big hit.

FIONA: In late January 2015 there was a large storm that came across our region and at that time of the year it’s really worrying if you get lots of lightning and no rain that follows and that’s what happened.

It was just a rogue spark that grew and it continued to grow and then everyone became aware that it was coming towards us, so we were surrounded. But no one knew of the impending danger.

SCOTIA: Lightning had struck a tree. It escalated into a bushfire.

FIONA: When I start talking about I can really feel the fear. The fear comes with talking about fire of that sort of immensity. It’s the uncertainty. So you see these billowing smoke clouds they’re like a nuclear bomb blast that you know that you have read about and you imagine. It’s a complete sense of powerlessness because you have the police and the emergency services they sort of swoop in and you are disempowered. So you have to pack up your house and put what you care about into your car and you say goodbye. And you hope that you come back to a home that standing and it’s really scary when you hear on the news that your town won’t survive until the morning. But lucky for us the rain came in our town our town did survive.

FIONA: It was the largest wildfire that had occurred in the south west of WA in recorded history. It went for three weeks before it was finally put under control. It burnt a colossal amount of natural heathland and forest farmland. The impact was incredible.

FIONA: It takes a very long time for your sense of safety to return. I mean you just drive anywhere and there are reminders in the trees the burnt trees that will never recover and they are signposts for what has happened.

FIONA: So when you’re traumatised by something like a bushfire your experience is you’re so disempowered by it and you know you’re kind of closed into your own personal pain and it’s really important to start hearing the stories of other people to realise what is shared.

SCOTIA: Suddenly the art nature trail had renewed purpose. And this time people from the community who had not been involved previously, were inspired to join in.

FIONA: Older men, they don’t get involved in arts projects, but they got involved in this one. It meant something. We had more people wanting to volunteer than we could accommodate.

FIONA: So the people whose faces are cast have been affected by the bush fires, some of them were firefighters, some of them were people who lost their homes, some are people who lost their livelihoods. And all of us lost a sense of safety. It takes such a long time to recover.

SCOTIA: These are the black charcoal sculptures of the town locals we’ve been admiring. They were added to the trail in 2015, after the fire.

FIONA: It’s the perfect material to do a commemorative work about the impact of fire in the community, using charred timber. Charcoal. It’s perfect. The faces and the bodies look really serene, and it’s a contrast to the experience of going through fire. That in its wake there can be serenity.

SCOTIA: Fiona has thought a lot about this… the quiet recovery that happens in the wake of disaster.

FIONA: In the case of a bushfire the fire brigade is going to be there to put out the fire. But what happens after that. How does the community re-establish itself. How does it gain a sense of security and safety again reconnection that’s where the arts come in.

We are not necessarily frontline but we are certainly I think whatever the second line is we are essential. We are essential services for community health and recovery – absolutely essential.

SCOTIA: For 12 years now, Fiona has run the arts nature trail. In that time, she’s been doing less of her personal arts practise, and more arts managing.

On top of this, she’s struggled to find the balance between dealing with her community’s trauma and her own self-care.

FIONA: I’m challenged by the intersection between wanting to serve other people, serve the greater good, and looking after myself. I’m really torn by that. And so my arts practice is very much been like that – serving other people – but often the sacrifice feels a little too much.

SHONA: What does self-care mean to an individual for their own self. How do they find the time to do that in the complexities of everything else they’re doing. And then if an individual is working with an ensemble or with a community how does their sphere of self care extend into that ensemble and community.

SCOTIA: This is Shona Erskine, a registered psychologist and consultant who also has a background as a dance artist.

She works closely with organisations and artists, coaching them to build resilience and to enhance performance.

SHONA: I think the most common thing I think I see is burnout. So individual artists will burn out. They haven’t done enough rest and recovery and their adrenal system it’s just been on for too long. And then you see a number of symptoms. So for example people are tired, they’ll report a complete lack of motivation for what they’re doing, they’ll have fallen out of love with their art form or being involved in projects. They’ve lost that sense of joy and spring in what they’re doing.

SCOTIA: Fiona knows what it feels like to lose sense of what made you fall in love with a project in the first place.

She was living through the effects of working with a traumatised community, while also being a part of that traumatised community.

It’s not uncommon for artists to occupy this dual space.

They are often activated to work with their own communities in times of recovery. The impacts can be intense, and usually without access to the psychological services available to other support agencies.

SCOTIA: What would you see as the support needs or the gaps that an artist might be experiencing.

SHONA: So there’s a difference between running arts project to make a work of art and running an arts project for all its therapeutic benefits. They’re two different things. What’s interesting about people who will go into communities that have experienced a level of trauma is going to be a lot of overlap there for them.

What I see in the arts which I don’t see in any other context that I work in, is the preparedness of the individual to put themselves under duress, under distress, in pain, in order to be able to do this thing that is really really important to them.

And this neglect of the psychological domain when people are handed a project that has huge psychological territory happening, and they’re expected to manage it, I think can also create problems for that individual and the community as well.

FIONA: Look there are some really good things about being an artist on the ground from the community that’s traumatised because people know that you understand their pain or understand it an element of it because you’ve been through the same struggle. But the challenge in that is that you also tired and you are also wounded and you’re also in pain.

SCOTIA: Of course, working within your own traumatised community is one thing. But working with trauma in a community that is not your own presents its own set of challenges. We’ll come back to Fiona in a moment.

Karen Hethey is an artist working with community. Her practice draws on a professional background in puppetry arts, performance making, intercultural community arts and applied Anthropology. She has 28 years of experience working collaboratively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across remote, regional, and urban Australia and also with regional communities to create community stories and performance projects.

Karen believes an artist’s role in a community is unique. She describes it as a therapeutic process where artists lift people from the ordinary to the extraordinary.

KAREN: It is different from the individual therapeutic space, but it’s a community therapeutic space. But it’s also art, and it’s genuine art, it’s why do art, why we put lines on caves when we first began, and why we still put lines on walls with spray paint. We’re artists, we express our humanity.

SCOTIA: Karen started out in the 90s working on early land rights cases. She came to see that through the arts, we can create an environment for understanding. A space to hold people, hold their stories and deepen the level of trust following trauma.

KAREN: And it was very very challenging and difficult times, and of course getting very burnt out as a young person and seeing right on at that time definitely the frontline of trauma and the legacy of the history of the impacts of colonial invasion and yeah just the absolute absolute decimation of people but also the resilience of people. So for me I was very burnt out very ill very sick after I’d left there, and completely burnt out by 26.

SCOTIA: Over many years Karen has continued to work as an artist in remote and trauma affected communities. She believes that when artists hold story for people and communities they are exposed to all sorts of realities that can be challenging to deal with.

Artists are called on to witness trauma and are asked to – what Karen calls – “reconcile the irreconcilable”.

When they’re in these situations and working on these projects, artists need support to address the impact.

KAREN: We work from a vulnerability in the same way quite a lot of therapeutic space happens and works and we have to work from that space. We have to work with vulnerability. And of course all those other… being able to step away but you can’t always step away you’re not always in a context because you’re immersed in it you can’t always step away. So that’s that’s a big challenge.

SCOTIA: Karen says it is imperative we find sensible ways to systemically support artists going into trauma spaces.

According to Karen, the ideal model of support has three components: access to a peer network; professional supervision; and crucially, professional development for context and preparedness that takes place before artists go into communities.

KAREN: I think there is a real need potentially from an organisational consideration that putting artists into the field who may be inexperienced it’s really important to have some level and scale of professional development where those artists get to talk and experience from others and a level of preparedness of these are the things that you may well experience in these contexts you may have these reactions you may have these responses. If that happens these are certain things you may need to do and call upon others to then manage that.

SCOTIA: Karen’s one of the artists who come to the ‘Making Time’ self-care retreats that we run at Creative Recovery Network.

They’re tailored to community cultural development, or CCD, artists

KAREN: And I think one of the wonderful things about the forums the self care retreats making time retreats is that they’re open to a range of experience of artists and practitioners and people working in CCD and pure artists as well which is a really rich forum.

SCOTIA: The retreats give an opportunity for reflection, extending notions of how we build self care into project development and management, ultimately giving people who work in high stress situations time to be with themselves in a nurturing and supportive environment.

Together facilitators and participants built a toolkit of resources, collegial connections and plans for ongoing peer support.

They also encourage artists to become self care activists – equipping them with skills and information to make systemic change, not just individual change. Ensuring that they can model self-care for the wider community.

SCOTIA: So what can people like Karen and Fiona actually do to address their well being as artists working with trauma-affected communities?

SHONA: Self-care is one of these things where we actually all know the rhetoric. It’s sleep exercise and food nutrition. And essentially they’re going to be different for every single human being but they’re going to be about a change to behaviour that it moves away from the person’s normal. So someone might sleep more but they might sleep less. They might eat more but they might eat less. They might eat less but eat more sugar. They might watch more social media and videos or they might become more isolated from people, they might use drugs. What we’re interested in is people knowing themselves when they are not under a huge level of stress and then being able to clock it when they are. So there is certainly a level of self recognition within that.

SCOTIA: Fiona was able to recognise that she was feeling worn out from the enormity of the Nature Trail project. Too much management and not enough creative fulfilment. She decided to make some changes.

FIONA: If I’m supposed to be role modelling the value of the arts for creating wellbeing for my community then I really need to start by looking after myself, and I think I am definitely getting better at doing that. And part of that journey of late has been really thinking about the language I use when I talk in my own head to myself but also when I talk to other people about what I do and trying to find ways that are more like a much more positive frame and not to be a victim of my own choices.

SCOTIA: Individual artists can recognise the need for self care. But if we are placing them in the pathway of trauma, it’s important that they are not solely responsible for their well-being during a project. At Creative Recovery Network we are working to address the need for more structured organisational support and collaborating with our colleagues to make it a reality.

SCOTIA: So how do you think we collectively as a sector can start to sort of pack in and balance that responsibility?

SHONA: There is a line of dialogue in the community that says if you as an artist just manage yourself care better you’ll be better off. And of course I can’t manage yourself care for you because self-care is for you to do. So you know it’s really easy to put the responsibility of personal self care onto someone and be naive about the context in which they are operating because you can’t always do self care during the project. The skills that you might develop around self care are actually ones you have to do outside of the project because once a project kicks off you are on and you’re on then and it just escalates through to the production or the culmination of the project.

So how do we prepare artists for that, what structures do we put in place for them, and then what acknowledgement do we give them that self care is actually a really intensely challenging thing during a project that you want to execute well. And so then, how do we help you recover afterwards.

SCOTIA: In other professional sectors associated with trauma, there are mechanisms in place to support workers. One mandated programme implemented is Professional Supervision.

SHONA: It’s one of the mechanisms in which people registered with their profession maintain a level of currency in their practice. And professional supervision allows you to reality test your actions meet with someone more experienced listen to their guidance test your decision making and also to gain skill in the area that you need to gain skill in.

SCOTIA: Access to this model of engagement is still lacking for artists. Shona is working with us to develop a professional supervision model to support artists in their practice and self-care strategies.

SHONA: So you’ll have a certain number of peer supervision hours which is sitting down with one or more people looking at your practice and other people’s practice and providing suggestions or advice on increasing your knowledge base around it and the other part of it will be active professional development which is where you go to a course or you’ll learn specific skills that then allow you to come back and practice in that area of expertise.

Professional Supervision and Peer Support can both work to relieve the artist of some of their self-care burden. It’s important to not feel alone. Here’s Fiona again.

FIONA: One of the things that’s really helped me understand what I do and why I do it is talking with other artists and arts workers from regional communities and realising that I am not alone and I am not unique in the amount of time I volunteer for my community and discovering that people are doing this all over the country.

SCOTIA: Practice methods, professional development and peer mentoring networks need to be developed and strengthened to support and sustain the well-being of artists and the people and communities they serve.

Unless the necessary resources, accountability and authority are provided, adequate supervision is unlikely to occur, as supervision will become a low priority under conditions of resource scarcity.

Supervision and professional development around self-care is a crucial part of reflective practice. It’s vital for the growth and sustainability of our sector. This means dealing with these issues in bigger, structural ways and building cultural capacity so that when disasters hit communities, their artists are ready and resilient.

FIONA: Emergency services make sure there’s preparedness for bushfires and floods and things like that but we also need to be thinking about is our cultural infrastructure ready for emergency. I think that that’s not done.

SCOTIA: Creative Responders is an initiative of the Creative Recovery Network hosted by me, Scotia Monkivitch.

This wraps up Season 1 but we’ll be back soon with a series of conversations with creative responders working in the field.

Thank you to Fiona, Karen and Shona, and Community Arts Network WA for their ongoing support and partnership with the Professional Supervision Pilot.

The series is produced in collaboration with Audiocraft, with Executive Producer Jess O’Callaghan, producer Selena Shannon and Creative Recovery Network project manager Jill Robson.

The Sound Engineer is Tiffany Dimmack and Consulting Producer is Boe Spearim.

Original music was composed by Mikey Squire.

If you are interested in supporting your community in challenging times, we would love you to join us by becoming a member of the Creative Recovery Network. You can sign up on our website.

You could also connect with us on facebook, or follow us on twitter and instagram.

We’d love you to tell your friends and colleagues about the podcast – you can find it in all the podcast apps and you can also listen at our website – just go to Creative Recovery dot net dot au forward slash podcast. This is where you’ll also find links and resources for further reading about what we’ve covered in this episode.

The Creative Recovery Network is assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Thanks for listening.

FIONA: think self care as an artist is a continuum. I don’t know where I am at on the continuum. I think I am in a better place than I was when I first started 20 years ago. But I think I’ve got a lot of work to do really. That’s the truthful answer.

How to Listen

You can find Creative Responders on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite podcast app. You can also listen to all of our episodes right here on our website and access transcripts and resources related to each episode.

Case study library