Storytelling in a changing climate: Indigenous art and tourism on the Great Barrier Reef

The climate crisis is one of the greatest disasters we may ever witness. In the face of such enormous challenges, what is the place for creativity and storytelling?

In this episode, guest producer Nicole Hutton takes us to the Great Barrier Reef to hear how reef coast Traditional Owners are using tourism, art and storytelling as a proactive tool to open conversations around climate change.

Nicole takes us out on the reef with Indigenous tour operator, Dreamtime Dive & Snorkel, to speak with Dustin Maloney about sharing stories from the reef and how Traditional Owners being in control of tourism happening on their own country is a critical step towards climate justice for people on the frontlines of climate change.

She visits the Hope Vale Arts and Cultural Centre where artist and Dingaal clan Elder, Gertrude Deeral, shares some of the ways elders in the Hope Vale community have utilised art and storytelling as a way of passing down complex layers of knowledge about their country, ecosystem and culture.

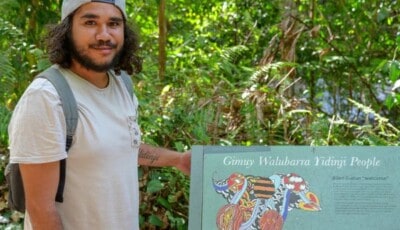

We also look at some of the tensions between tourism and conservation and hear from Jiritju Fourmile, a Yindiji man from Gimuy, Cairns, about coral bleaching, the cultural significance of the reef and the importance of storytelling and tourism in generating a wider understanding of the need for its protection.

Interviewees:

- Dustin Maloney, Dreamtime Dive & Snorkel

- Gertrude Deeral, Artist, Elder from the Dingaal clan and Traditional Owner of the country around Lizard Island

- Jiritju Fourmile, Traditional Owner and climate activist

Production Credits:

Executive Producer: Jess O’Callaghan

Producer: Nicole Hutton

Edited and Mixed by: Tiffany Dimmack

TRANSCRIPT

Season 2 Episode 3: STORYTELLING IN A CHANGING CLIMATE: INDIGENOUS ART AND TOURISM ON THE GREAT BARRIER REEF

Crew Member 1: With the vessel guys, you are in enclosed spaces. Please ensure Covid safety. So you’ve seen our hand sanitising stations around the vessel. Every time you jump in the water, the crew will be going round and sanitising the vessel. If you have any issues with that, guys, please feel free to come up to any of us

Scotia: Producer Nicole Hutton is on a boat, heading out into the ocean just off Cairns.

Nicole: It’s full of families and tourists, all hoping to catch a glimpse of the world famous Great Barrier Reef.

Crew Member 2: We are moored up at our beautiful marina on Gimuy Walubara Yidinji country. We also have Mandingalbay Yidinji on the side. We have Irukandji off to the far beaches here and then passing these corners out here. We’re gonna head to Gunggandji. Right. So Gunggandji sea country today, guys. Make sure you are using all of our recycle bins. All of our bins putting all of your rubbish away. I know we’re still on the boat, but a bit of wind can pick up any piece of rubbish and get it into the water.

Nicole: I’ve been told it’s the perfect weather to visit the reef. This boat belongs to Dreamtime Dives.

Crew Member 3: How’s everyone feeling today, Issac I think my ears are blocked again hey. It’s a bit weird? Guys like Sam said, you’re going out to the Great Barrier Reef, right. So are you guys excited for today. That’s how we’re going. All right. By the end of the day, I’m going to get all you guys screaming. Is everyone alright with that?

Nicole: It’s an Indigenous tour operator up here on the Reef. Each trip to sea is a mix of culture, storytelling and tourism.

Crew Member: All right, guys. That’s our crew. And we’ve all been given permission by the four Traditional Owner groups to share their cultural stories, their cultural connections to the land from thousands and thousands and thousands of years ago passed to us and hopefully passed to you guys today. All right. So don’t be hesitant to ask any questions

VO: I’m Scotia Monkivitch… and this is Creative Responders, a podcast from the Creative Recovery Network that explores how creativity and the Arts have a unique role to play in disaster management.

This episode, a story from producer Nicole Hutton.

Nicole is a young Aboriginal woman from the Garawa people, and she has spent the past four years working with other First Nations people to educate and campaign to mitigate climate change.

Nicole: There’s a huge role for art and storytelling to play in that fight.

As I headed out to sea with Dreamtime Dives, the water around me was pristine and flat.

Underneath the surface the reef is teeming with life. There are thousands of organisms that call the reef their home.

But as the climate changes it puts the reef under stress. I went North to find out how reef coast Traditional Owners are using tourism, art and storytelling to educate people in order to protect the Great Barrier Reef.

Scotia: As we see the increasing impact of compounding disasters, the inherent link to climate change is being pushed to the fore in broader debate

According to a UN Disaster Risk Reduction Report released in October 2020, the climate emergency is growing and has caused the number of natural disasters to double in the last 20 years.

In presenting the report UNDRR Head, Mami Mizutori said “we are in the middle of the greatest disaster we and our children will ever witness – the climate emergency” and she emphasised there is no good disaster mitigation governance without climate action.

First Nations people have used storytelling for millennia as a way of sharing complex layers of knowledge about living with and caring for country.

How do we centre First Nations knowledge in understanding the interconnectedness of country, arts and culture?

In the face of climate change disrupting the deep connection between land and people what role can creativity and storytelling play in this vital work?

We asked Nicole to help us explore how First Nations stories not only share cultural heritage but can also be used as a proactive tool to open engaged conversations around climate change.

Nicole: Growing up in Townsville, North Queensland, I learnt to respect and treasure the reef.

But even though I heard stories, read books and watched movies about the reef, it still felt so far away.

For many people though, the reef is their home. This is Dustin Maloney.

Dustin: I’m a Kuku Yalanj Man and also a Yiginji man. But through my family’s ties I’ve got ties here also with the Irukandji people in Cairns and also the Gunggandji people over Yarrabah.

Nicole: Dustin’s an Indigenous Tourism Guide for Dreamtime Dives.

Dustin: What makes us different from the tourism industry up here in the far north is we have a cultural content that we provide throughout the day. So we share stories, local stories of the area. We work alongside, we have our own marine biologist department also. So we share some of the scientific facts about the reef. We get to show and demonstrate how some of our props that we use, like, for example, the didgeridoo, the clap sticks, our spears and shields, we actually got these things on board to show them what types of different materials that we actually use on a day to day basis.

Nicole: Culture, geography, science, it’s all part of the experience, but a huge element of these trips to sea is hearing stories.

Dustin: I just look at it as me telling them a story and they’ve gone home with something to remember, not only from what they’ve seen but also from what they heard. And that makes me feel good because I’ve told a story and that story is going to stick with that person for as long as they can remember.

Dustin: The main thing I like to get across is no matter where you go in Australia, Aboriginal language was never written down. We did not have a written system for our language. And the only way we would actually share our teachings and knowledge is through our stories and through our dance. That’s the main thing I like to get across. A lot of people are fascinated and it goes to show how our knowledge gets passed down from generation to generation.

Nicole: And the one that stays with you long after you leave the boat is the story of how the reef was formed.

Dustin: Where you see the shoreline is today was way further back. It was back to the continental shelf and all the area from here out to the continental shelf, it was all liveable it was big grass bushlands area and belief goes that one day a hunter from one of the tribes here, actually, his tribe was actually going through a little bit of a starvation period. So what he did was he asked permission from the elders to actually go along the coastline at the shelf to get some food to bring back for the tribe. And they told him, yes, you can, but there’s one animal you cannot touch. And they told him it was the black stingray. So he said, OK, well, he went out and made his journey out. He went fishing all day. He was just coming down to the end of the day now and just coming off the end of the day. The sun was a little bit just setting. There was a little bit of a glare in the water, but he seen something move so he shot the spear at it. He didn’t realise what it was until he got up close to and it was the sacred fish that he couldn’t touch. So with that, because of that, the stingray itself started flapping its wings. And with that, the water started rumbling and it started to rise, rise up. So the huntsman, he went back, made his way back to the tribe. He informed the elders of what what happened and what he had done. So what they did was actually lit up big boulders and actually rolled them into the rising sea. And that actually stopped the reef, the water from rising up and these big chunks of boulders that actually rolled in are the big patches of reef that you see in there today. And that’s their vision of how the Great Barrier Reef came to be.

Nicole: Hearing stories like this told by Traditional Owners of the reef, I felt deeply lucky. Lucky that I’m traveling and listening to stories from First Nations people from different clans and tribes.

As an Aboriginal person I know how sacred our stories are to our culture, they are sacred stories that connect us to ancestors from many generations ago.

The parts of the reef I went to on the tour were beautiful and vibrant. But elsewhere, the reef is in trouble.

Dustin: So with the coral bleaching, it depends on the water temperature where you’re at, if it goes higher than a certain temperature, the coral actually gets stressed out and once the coral polyp rejects the algae, yet that’s where you get the coral bleaching. That’s why it just turns white.

Nicole: Coral bleaching. It’s often a controversial topic that you hear discussed by politicians or something you hear about on the news.

Pictures of stoney white coral have come to represent the parts of our environment we won’t be able to get back once our world heats up.

The reality of bleaching on the reef is that it comes in cycles similarly to other disasters.

Climate change is threatening to make those cycles more frequent and severe. If we continue in the direction we are heading, we are exposing the reef to more bleaching events in the future.

The reef is not dead, and in many places the reef is as vibrant as ever.

But we need to take action now to protect the future of the Great Barrier Reef and all of the organisms living in it.

The First Nations people who live on the Reef know how far-reaching the impact of a damaged reef would be.

Dustin: it’s very important, actually protect the reef, the reef is a good place for providing for food. Like, for example, if we lose the reef, we would lose our fishing industry up here also. And not only that, but the cultural flow, we’ll actually lose a bit of a peace, peace inside of us. The Great Barrier Reef is the biggest living organism in the world, and we get it here in our front yard. And if we lose that, we’ll be losing the best part of Queensland I’d say.

Nicole: I’m inside the art center and it’s so fresh and open and you can see so much of greenery outside. Wow. They’re so colorful.

Gertie: I just got only one here. All the rest gone. I think one. One. Yeah. One, two. One, two, two.

Nicole: Which ones are yours?

Gertie: One of this. This one here.

Nicole: In the fight against climate change, storytelling and art can be a powerful weapon.

Conversations about climate change can be difficult — people have fiercely-held opinions, across the political spectrum. The radical changes needed to tackle this global problem are hard to grapple with.

Art creates a space to bring nuance back into those conversations. It’s a way of hearing each other’s perspective, promoting action and understanding in these difficult spaces.

The power comes from sharing ideas through connection and conversation.

It’s really apparent up north, particularly when it comes to the relationship people there have with the land and the reef.

I’ve come to Hopevale, north of Cairns, to visit the Hopevale Arts and Cultural Centre.

Aunty Gertie is showing me around.

Gertie: my name is Gertrude Deeral, but my maiden name was Getrude Simon. I was born in Woorabinda.

Gertie: We do it there. We just sit down there and, you know, dye. Put it in the thing and hold it when it’s dry we take it, the girls put it out there, hang them on the line. So they put chairs, you know, put chairs there, make this table bit longer, sit down there and do our work. I always be on that side.

Nicole: Aunty Gertie is a talented artist, and her paintings are showcased across the country. They’ve also been turned into dresses.

The art centre sits in the shade in the middle of Hope Vale. It’s the kind of place where I would like to pull out a chair and sit under the leafy trees.

Inside is fantastically decorated with one half dedicated to the artists and the other half a gallery with bright dresses and materials hanging up for sale.

Aunty Gertie shows me a colourful balcony that contrasts against the bright green grassy backdrop.

Nicole: The balcony is so colorful. It’s all painted rainbows.

Gertie: That’s what I want to do with my verandah at home. Painted like that rainbow color.

And paint the floor. You know, but I was up and down. Was up and down, you know, up there coming back again.

Nicole: The art centre is clearly the heartbeat of Hope Vale. It’s filled with children and families.

Nicole: Well, thank you so much for showing us around. Lovely. It’s so lovely here.

Nicole: Aunty Gertie’s family live further north, and when she leaves town to visit them, the thing she misses most is the Art Centre.

Gertie: We missed it. We always sit down. We miss going down. That’s just the place for our meeting. We’d meet and get together. And we love it. Meeting here, we sometime buy maybe meat or something cook it here might do something stew or something and serve it outside. We have a good feed.

Gertie: So they bring fish. Turtle to cook it and we have a good old feed.

Nicole: It’s a place where the community come together and do what they love most: Paint.

When we talk about painting Aunty Gertie has a broad grin on her face. It’s clear how much this place means to her.

She first started painting when she was young.

Gertie: When I was a school girl, in school, I used to paint. That’s how I learnt people liked mine, paintings. I was surprised I would go this far.

Nicole: Aunty Gertie and other women from Hope Vale sit around the arts centre, painting together. Their favourite things to paint are the country, animals and plants of the reef.

Gertie: Well, they started first. We got together and they sit around outside and painting.We are happy. All the ladies here. Happy. I joined them here. Every morning they come down here and paint. From Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday – Thursday is our shopping day.

Nicole: When she was young Aunty Gertie spent a lot of time on the reef.

Gertie: Now, my mother is a Tullum* Person, Tullum* Is the reef. That’s her custom, culture and we call it Tullum* person. That’s mother. And and that’s how I learnt you know, I go out reef fishing when I was small and we used to dive underwater, look around, you could see down under reefs, pretty. Yeah right out to sea, that’s a Great Barrier Reef they call it, right out. But we just go a little bit in lot of reefs out there. But now, I’m scared. Too many crocodiles and sharks. I’m scared for the wave might kick me over and I will get drowned.

Nicole: Now that she’s older and doesn’t go out to fish on the reef anymore, one of the last connections Aunty Gertie has to the reef is painting what lives in the ocean there

Gertie: Animals in the sea that lives there, corals, fish, turtle, dugong, whale, sharks, all those, you know, what I see.

Nicole: Like Dustin, art and story is about more than creative expression. For Aunty Gertie, it’s about memory.

Gertie: It’s important for us and to teach our young generation. When we go, all our children can look after the, you know, our kids. The next generation, you know, they go out hunting with a boat, go turtle, dugong. And that’s how they live. Feed on, their living from fish, dugong, turtle.

Nicole: To Aunty Gertie and the people of Hope Vale the art centre is capturing their stories and displaying them to the rest of the world.

Gertie: I made some materials. Paint you know what we want to draw. And then we’ll put it on material. And they do it down there for us because we haven’t got any things here to do that we just give our drawings and things to them. They’ll get…buy materials from they’ll print it for us. And someone bought the lovely material and told Melly, it was mine. They they got the material for the hospital. They got it on the windows and on the shower curtain.

Nicole: Through art, these stories of the reef reach a wider audience.

Aunty Gertie’s work has appeared across the country and even had some huge international recognition.

Gertie: This is another one of mine. The same one, I got only one, two and three.

And these are what is this a um. The same one wattle.

Nicole: Pants?

Gertie: Yeah, they pants.

Nicole: Who makes the pants?

Gertie: They make it down in Brisbane.

Nicole: There’s some beautiful green pants with white drawings of wattle on them that’s so amazing.

Nicole: And this is a dress.

Gertie: Yes that’s a dress.

Nicole: Wow. That’s so cool. It’s a red dress with the wattle.

Gertie: And they down in, where’s that place in Brisbane. You know that what they had down there. Olympic, some of the girls wore my dress.

Nicole: On a catwalk?

Gertie: Yeah.

Nicole: Oh really. Did you watch it?

Gertie: No, we didn’t go down for that. They they wore it for that Olympic you know.

Nicole: Oh Olympic?

Gertie: When they had that Olympic down, I don’t know what they had.

Nicole: Oh what is it? The Commonwealth Games?

Gertie: Commonwealth yeah.

Nicole: They wore it at the Commonwealth Games?

Gertie: Yeah the the girls dressed up in the modelling.

Nicole: Really? Which was it? Which drawings was it? These wattle…

Gertie: Wattle, I think that dress that dress, this is the wattle. Wattle, you know it’s out in the bush. It’s a yellow. The yellow and that you know, wattle tells us about when the thing’s are fat like a fish and all those fish turtle, all those that tells us the fish is fat. We can eat it.

Nicole: Hearing Aunty Gertie tell me this story, I’m hit with familiarity.

I’ve heard stories many times from family members, elders and community members who have told the stories of the importance of flowers helping people hunt.

They tell me that the seasons have started changing. Flowers are coming later and things aren’t as in sync as they used to be, people can’t rely on the methods that have been used for thousands of years anymore.

This story is similar for many First Nations people across the country and it’s caused by the same thing: Climate Change.

It’s people like Aunty Gertie who have seen these cycles shift over generations telling these stories of change. Now, it’s young First Nations people leading the charge when it comes to climate justice.

Jiritju: My name is Jiritju Fourmile, Yindiji Man here located in Gimuy, Cairns.

Nicole: Jiritju and his family have lived here in Gimuy for generations. Now Jiritju is standing up as a leader in the fight to mitigate climate change and protect the Great Barrier Reef.

Jiritju: Well, the reef not only just important to myself, but everybody that lives on the coast, I think it’s just important to me just because as an Aboriginal person, we see it as our lifeline, like we see it as a supermarket where we can get fish. We can also get medicines from the reef as well. But also just helps sustain the way of life, I guess. We use it for fishing, hunting, gathering. We’re usually out there every day. If not, if we didn’t have to work, we’d be out there every day. I know I would be. But yeah, yeah, we’re pretty much just fishing or getting crayfish, or getting clams or anything else that you can really get your hands on really.

Nicole: These changes in nature, in the seasons and the environment, he’s seeing them play out on the reef. On land, wattle blooms early, and under the sea, coral turns white.

Jiritju: Well, with the changes that I’ve seen personally, just a lot of the coral die off and the bleaching events have been happening yearly and stuff like that, just a lot of species dying off now of coral and also the fish life that’s around – personally starting to see a lot of like the sea life we used to be able to go to one fishing spot and there’d be a variety of fish. And now you’re only seeing like two sort of species left there.

Nicole: Jirituju was a teenager when he first noticed the bleaching.

Jiritju: The first time I heard about coral bleaching, I was a bit younger than what I am now. I was still in my teens and I didn’t fully understand what was happening. I was just like, ok the bleach in the coral. I thought someone was actually like tipping bleach on the coral, and then read up on it when I was older and I was like oh it’s actually the warmer waters and stuff like that. I was like we need to do something about this.

Nicole: The stories we’ve heard about the reef already tell us about its history.

But there’s another story being told, about it’s changing.

Jiritju: Storytelling’s just a big part of our our culture. Being Aboriginal and being an indigenous person, just like it is in any other indigenous culture. I guess, that storytelling brings people closer together. It’s a oral history as well. It’s also a record of what’s happened, detailing things that’s happened as well. I just like storytelling just to talk sometimes, but also just to spread the message about what’s happening. You know, like, locally around here as well. Yeah.

Nicole: Those stories impress upon the listener the importance of caring for the reef, but they also stress the connections between the land and the reef.

Jiritju is also an artist.

His artwork is a modern representation of their community’s ancient creation stories.

Jiritju: The only artwork that I have now that’s visible to the public is up at the Crystal Cascades and that’s just talking about our creation stories of the Crystal Cascades and how that was formed. But in saying that with Crystal Cascades as well, that’s another life line that runs out to the reef as well.

Nicole: Jiritju’s own community isn’t learning of this story from visiting the Crystal Cascades. This art has a different purpose — to stress that connection to the people who visit the area.

Jiritju: A lot of tourists go there, yeah. So it’s important that we spread the message to tourists and people that are visiting these areas to be respectful and clean up after themselves when they leave.

Nicole: Coral bleaching has been bad news for reef tourism. One 2018 survey claimed that the Reef was no longer among the top 10 reasons for Australians to visit Cairns.

But for locals, tourism is a critically important part of the community. It’s critical to the local economy, but also in sharing the stories of the reef and generating a wider understanding of its cultural significance and need for it’s protection.

A lot of work has been done by tourism companies to demonstrate how much of the reef is still beautiful.

This is where the conflict between conservation and tourism begins.

Tourism brings money into the area, but doesn’t come without its own harm.

Jiritju: It’s a blessing that we get to see all these people from around the world to come and experience my country that’s here in Cairns or Gimuy. But the curse also being that we get a lot of traffic here as well. A lot of foot traffic. And whether that being the boats in and out onto the reef or a lot of foot traffic out into the Daintree or into the rainforest here. So I think it’s just people need to keep in mind when they are coming here, although it is a tourist hotspot, that they are responsible for what they do when they come here and to have that in mind. So, yeah. I think just for tourists to have in mind that when you’re visiting Australia and you’re visiting these local places that are that aren’t close to the big cities, they’re off the beaten track a little bit to be mindful that you are going onto sacred land sometimes and to seek the indigenous people that are there and to get permission as well. It’s a big part of our culture, getting permission to be able to stay on the land.

Tour Guide: This is Great Barrier Reef. So that means it’s quite important right. We have some of the best biodiversity in the world. We have so many pieces of coral, different types of fish. Got turtles. Who likes turtles. Anybody like sharks as well?

Crowd: Yes!

Nicole: My whole life I have learnt about how the rapidly changing climate would impact the world ‘one day’.

It’s only very recently that I realised that no longer are we waiting for ‘one day’. That day is today — bushfires, droughts, heatwaves and coral bleaching are all the result of climate change.

As a young person I understand how critical it is to make sure that we can pass things on to the next generation in the same condition that it was handed to us. It’s completely possible.

Bleaching is a cycle and it’s not happening all the time, but the more frequent the bleaching events are, the riskier it is for the reef.

Dustin: With coral bleaching, the last biggest one that we had, was during when Cyclone Yasi rolled through. It was a little bit warmer than expected and that cyclone came through and it actually destroyed a lot of the reef in certain areas also. But, yeah, I think that was the last, last big one and from there, it’s been just tragedy going up and down, especially around summertime when the water really gets a little bit too warm, you know.

Jiritju: For the future, I hope that the reef is still there, not only for my daughter, but for everybody as well to enjoy, because it is a very beautiful sight to see, especially when all your coral are in full bloom and it’s really bright and there’s a lot of life and there’s a lot of fish swimming around. And you can see a lot of turtles as well, just a lot of the marine life about. It’s really lovely, especially when if you’re diving. It’s another world under the water. Like you block out the civilisation that’s around you and all you can hear is that real silent, you know, but it’s beautiful, that silence. It’s really nice. Yeah. I hope that the reef is there for my kids, but also for everybody else to enjoy as well.

Nicole: Visiting and talking with so many First Nations people while recording this podcast taught me so much more than I ever expected to learn.

Climate change is a huge threat both to the reef and to tourism. For reef coast Traditional Owners, being in control of the tourism happening on their own country is a critical step towards self determination.

This enables greater cultural control in the face of climate impacts and centres Indigenous-lead sustainable mitigation programs.

And for people like me, who have always dreamed of visiting the reef, I am glad to know that there are First Nations leaders to show me around.

Tour Guide: Sadly, we’re gonna have to say goodbye to you fullas. We’re a bit teary eyed. But guys don’t cry just yet.

Tour Guide: Hey guys we were just on the Great Barrier Reef. All right. What you guys learned today?

Passenger: Lots!

Tour Guide: Lots? You guys learnt lots? All right. Well, you guys learnt lots so I want you to feel that. Feel all that alright.

Nicole: Being able to put on a scuba suit and dive down under the water and see the reef close up was one of the most incredible experiences of my life.

The silence down there made me feel like I was entering another world. One filled with colour and crawling with life.

Seeing this place up close and hearing the stories from the Traditional Owners just made me want to fight to protect it that much more.

Through art, through tourism and through the history and creation of the reef what’s most important is storytelling.

It’s these stories that touched my heart and reminded me how important it is to protect the reef.

It’s an incredible place and one day I want my grandchildren to be able to visit and see how beautiful it is.

Tour Guide: I want you guys to put on your own energy and let it out. All right. So would you guys like a farewell?

Crowd: Yes!

Tour Guide: That’s it. That’s it. Oh, I’ve got a ring in my ears now from that. That’s awesome. So as you guys know, we’re a very loud boat, so we want to make sure all these fullas in this marina know that we’re back home. You guys ready for that?

Crowd: Yeah!

Dustin: The most basic way I can put it as if you look after land and sea – in return it will look after you. And not only for yourself, but for the next generation that comes along. For example, if you have a you have a nice home and you have a nice beautiful front yard and if you let that yard go, it’s not going to look good. If you maintain the area and cut back the weeds and whatnot, it’s going to look beautiful, like for everybody to see.

Tour Guide: Are you guys all ready for that? So my two brothers here are going to dance for us. Me and Laurie go start the clap sticks. You guys remember the beat.

Tour Guide: I’m pretty sure you guys are Indigenous hey. You guys are so lovely. All right, guys, are you guys ready?.

Crowd: Yeah.

Tour Guide: My brothers are you ready?

Scotia: Creative Responders is an initiative of the Creative Recovery Network hosted by me, Scotia Monkivitch. A special thanks to Nicole Hutton for producing and co-hosting this episode.

Nicole: We’d like to thank Aunty Gertie Deeral and everyone from the Hope Vale Art & Culture Centre, Jiritju Fourmile, Dustin Maloney, Trevor Tim and the rest of the Dreamtime Dives crew. My parents who helped me record Jean Lewis and Earl Hutton and all Traditional Owners who welcomed us and showed us around their beautiful country.

Scotia: Creative Responders is produced by me and my Creative Recovery Network colleague, Jill Robson;

in collaboration with Audiocraft, with Executive Producer Jess O’Callaghan and Sound Engineer Tiffany Dimmack.

Original music was composed by Mikey Squire.

If you are interested in supporting your community in challenging times, you can find out more about what we do at our website Creative Recovery dot net dot au or connect with us on facebook, twitter and instagram.

The Creative Recovery Network is assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Next episode … we revisit the theme of self-care for artists and community workers in remote or disaster impacted communities with the team at Wilurarra Creative.

Silvano: One of the other challenges, but also one of the other awesome things about remote life is that you are part of a community. And so the line between professional and personal is is almost non-existent. And in fact, for you to do your best work, it has to be blurred. So, you know, because for Ngaanyatjarra communities, everything is based on relationships. …And that’s the most important thing. …

Thanks for listening.

* Tullum: The transcription of this word was not able to be confirmed with Aunty Gertie at the time of publication and may not be correct. An updated transcript will be provided.

How to Listen

You can find Creative Responders on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts or your favourite podcast app. You can also listen to all of our episodes right here on our website and access transcripts and resources related to each episode.

Case study library